. . . won't be applied in the case of the missing notebooks. Librarians in Cambridge are, au contraire, cock-a-hoop that two of Charles Darwin's leather-bound notebooks, half-inched in the 00s, have been carefully wrapped up and returned in a pink gift bag. Anonymously, of course.

We can't be more specific about exactly when the notebooks were stolen because the security systems back then was so full of holes that any bad-hat could drive a coach and horses through them. A 19thC metaphor for a 19thC mindset, when the only people who would want, or obtain, access to archival manuscripts were gentlemen and scholars. Theft being unthinkable the librarians assumed the material in their charge was somewhere in the vaults. It took Jessica Gardner the new, and less complacent, director in 2017 to insist on a root and branch search and conclude that the notebooks had been stolen. If this is ringing a distant tinkle, it may be because you read about in The Blob at the end of 2020.

Back in the 1970s when I was studenting in Trinity College Dublin I requested, for my own extra-curricular researches, access to a 17thC book. I was sent up to the rare books room in the old library and a while later, the book was laid on the table in front of me. There were rather strict rules and regulations about bringing ink anywhere near the old books and manuscripts. Presumably in the knowledge that at least some of the gentleman-scholars might have a palsy while filling their pens adjacent to the priceless ancient paper. It would have been difficult for me to stuff the book I was reading up my jumper when I packed up. In the regular TCD Science Library at that time before magnetic bleeper strips, it was easy enough to liberate a book; ask me how I know.

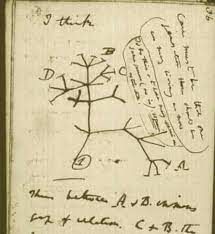

The missing Darwin notebooks were a particular loss because one of them contained the Great Man's most famous doodle [see L]. This 1937 tree-of-life pic is widely disseminated as an example of the process whereby the ghost of an idea is developed into a stated hypothesis which can be shared with the community and, importantly, tested. Darwin was notably engaged with his many children, dragooning them to help him catch and mark humble bees or collect worm-casts in the garden at Down House. At least some of the doodles in the Darwin collection were contributed by his offspring.

The collection in Cambridge is huge, and I'm not in a position to chide them for not knowing where every item is at all and any times. But it really is a lesson for folks like me, who have a lot of books - and eek scientific notebooks, me - to speculate on the utility of maintaining an extensive personal library. Lucky that I R retire and have time on my hands because I spend silly amounts of my remain time on earth trying to . . . find . . . that paper . . . which . . . I know is somewhere in the house.

No comments:

Post a Comment