A while ago, I was waxing all groupie about the August 1932 Genetics Congress. In those days, genetics was quite the exclusive field - in the sense that all the practitioners could cram into a large gymnasium. Now there are probably as many "geneticists" in Ireland as there were in the whole world 90 years ago. but of the few hundred attendees in 1932, most have sunk without trace: invisible to Wikipedia, absent from Pubmed, almost ungooglible. That's how it is: few of us in science really break the cage that constrains us and go explore really new fields. It's rather same old same old soon forgotten workaday make-work.

Sewall Wright's paper on adaptive landscapes was different. It set out a new, and very fruitful, way of imagining the world and individuals therein as they are buffeted by a hostile environment and try to make the best fist of their lives with the physical attributes and quirky behaviour they are dealt at conception. Wright simplified his ideal, theory-tractible world as a 3-dimensional landscape with living things scattered across it where the dice of genetics let them fall.

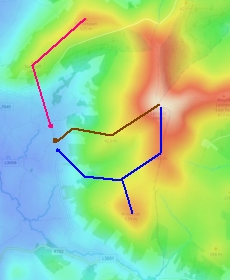

He imagined two people creatures starting off somewhere on the landscape and allowed them to shuffle about the landscape with a slight tendency to move uphill. But he also acknowledged that there's a gale across the land which blows you off course, and then disorienting fog comes down so you can't easily tell where up is. Up is the power of selection: the slight tendency to leave more offspring than your neighbour because of some heritable beneficial attribute. In the pic [L] two very similar creatures start off close together in the landscape. Actually it might be better to think of lineages rather than individuals. Ma does well and leaves her kids in a better place - further up the hill. The kids will trend upwards because of what they have inherited from Ma, but it will be fuzzy: there will be back-sliding and drift but the tendency will be Up].

By chance A and B move apart but still have an anti-gravity bias to moving uphill. They both eventually reach a peak of perfection at the top of a + hill. From that height they can do no better, every step will see them in a lower / worse position. BUT the hills are alive with the sound of inequality: A is well-satisfied with reaching a local maximum fitness; B is also at a local peak but it is 2 contours higher in absolute terms. B is fitter; A is doing well but is toting around a weird imperfect toolkit and is, frankly, a bit of a kludge. This way of thinking can help explain some of the WTF show-stoppers biologists encounter with any careful investigation. Think the recurrent pharyngeal nerve, male nipples, susceptibility to SARS-CoV2, all those work-days lost from lower back pain, the insane desire to go mountain-biking. Evolution is not about perfick; it's about good enough.

On the right is an actual topo map of the hills close to where we live. IF three walkers start close to each other on the road which skirts the uplands [as well-engineered roads often do] ANDIF each party moves only uphill step after step THEN they will likely all finish up on different peaks. Following this algorithm PersonBlue comes to a point where if they stumble left they finish up at the pico di tutti picos but a trip to the right and they will finish pretty high up and no way down but at an objectively sub-optimal summit. Anyway, I though it would be fun for a bunch of people who have heard of Sewall Wright to start low and head up and find out just how fit they are . . . on Sunday 28 August 2022: exactly 90 years after Sewall Wright presented his paper. Those gasping at a decision point can head for an easier goal or turn back for home and start preparing kebabs for the rest of us.

Now, I am fairly certain that none of my family could recognise a picture of Prof Wright if it jumped up and bit them; let alone explain to a six year old why he is worth commemorating. But I'd expect more from geneticists and evolutionary biologists. I was, therefore, surprised [and disappointed] at the reaction when I announced his March 1988 death at work. Work was the Department of Biochemistry & Genetics (in a different country) but only one of my colleagues knew about whom I was talking; and they were quite frankly Scarlett about the news. Wright was right, though, and his way of seeing the natural world was insightful and informative. See y'all at the end of August.

No comments:

Post a Comment