A. Why, of course, you'd grow up to become an artist and explorer yourself.

Of course it doesn't always work out like that: I didn't join the navy and was never in charge of anything, let alone a crew of 600 and 200m of warship. Travel, of which I have been a keen consumer, has involved far more turning the pages of a book than turning over vegetation to reveal leeches and snakes. The genre was given its modern timbre by a pair of books - Brazilian Adventure and One's Company - published in the 1930s by Peter Fleming: older brother of Ian "007" Fleming. Fleming is the quintessence of British stoic aplomb. Maybe not quite dressing for dinner in the jungle but having an unassailable gift for wry humour and intrepid pushing on because going back is really not quite the thing a chap does. After WWII, this mode of travel was carried forward, with some hilarity by Eric Newby and Redmond O'Halloran; and much later by Bill Bryson.

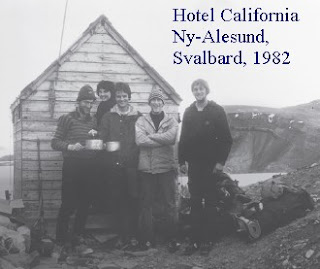

The picture at the top shows Tim Richards père and others outside their Arctic accommodation which is as big as the garden shed behind our house. That was the pot of nostalgic gold which defined the arc of Dan Richards fils trajectory. The thesis of his book Outposts is that striving for distant and inaccessible places can turn a spot-light on a pilgrim's mettle. Sometimes things only qualify as "fun" in the recall but if you never go near the edge you'll die anyway eventually; perhaps without having lived. The outpost-hopping starts repairing sæluhús with/for Ferðafélag Íslands - the Icelandic equivalent of Scotland's Mountain Bothy Association MBA. Sæluhús translates literally as joy-houses because that's what you feel when one of these primitive shelters is espied from afar through a break in roiling ground-level clouds; the alternative being either a) a bleak night's sleep or b) death by exposure. Later, he persuades a Scots pal to join him on a 150km ramble through the Cairngorms sampling the delights of the MBA's rough hospitality.

In between Dan tunes into Le Phare du Cordouan which features as a refuge in the film Diva. This is not inaccessible to anyone who can muster €44 and 4 hours for the jaunt from the coast of Aquitaine. But getting to the top gives a sense of achievement and allows the mind to reflect on what it must have been like when the West coast of Europe was the end of the world.

It takes a little longer to get to Desolation Peak in Washington state where Beatnik Jack Kerouac spent two month lord of all he surveyed as a fire-watcher in 1956. Kerouac parlayed that brief and somewhat unsatisfying experience into a string of best-selling books which dangled like a carrot in front of the next two generations of wilderness wannabees. Most of us cannot bear our own company for longer than a weekend and would go bonkers to be exposed to the social deprivation of solitary exfinement for weeks at a stretch. While there Dan gets to hang with Jim Henterley [prev].

After several other contrived adventures, the final chapter takes Dan to Svalbard but not as remote on that remote enough place to match his dad's furthest North at Hotel California. Here, after actually seeing a polar bear with two cubs, in their native habitat he reflects, not without introspection, on humanity's place in Nature. WTF is he doing hauling fat-arsed carbon footprint to the distant Arctic when the creatures he comes to see are done-for because the ice is melting from the collective carbon footprint. It's not "fine" but it is trite to make the connexion between flying and snow-mobiling to view the goddamn bears too direct. Bitcoin and FAANG is nixxing the ice far more effectively than all the destination tourists who have ever been to Svalbard. And you, yes you me, who are virtuously Friendfaceless and compost the carrot-tops . . . you'll have to give up the chest-freezer, the central-heating and the car before you can chid Dan for going to the World's End.

The adventures are "contrived" because this is Richards' fourth book and his idea needed a deal of research and forward planning to come off. It's an [ad] venture to invest so many weeks at a desk thinking what can be done with a finite budget and working out when and where is possible. And when all the travelling is done, many more weeks are required at the desk putting the pieces into a coherent order. But the jokes are not, cannot be, contrived: they spring spontaneously from the self-deprecating adversity in which The Plan has dumped The Author. I laughed: the baton has been passed from Fleming and Newby to another writer who uses travel as a way to explore what it is to be human and alive.

No comments:

Post a Comment