Yes, you read the title correctly, not beaten to death for being white or the far more common beaten to death for being black. That's one interpretation of how Ignaz Semmelweis [L] met his untimely end at the age of 47. But we'll start at the beginning because he was born Semmelweis Ignác Fülöp on 1st July 1818 in Buda on the West bank of the Danube - y'know: opposite Pest. Although his family was of German ancestry, his early life was spent in Magyar-speaking Hungary [or "in Hungary speaking Magyar"] where they follow the same patronym-first "Eastern"convention as they do in Kerala where my put-upon colleague comes from.

A bit of modern context. When I was working in St Vincent's Hospital more than ten years ago. someone on the wireless [Minister? Head of the Health Service?] suggested that it might not be a good idea for doctors to wear ties on duty because they were an obvious source of patient-to-patient transmission: getting dunked in some yeuch bodily fluid by accident and then dripping away through the rest of ward-rounds. That afternoon, I happened to overtake a couple of young doctors on the corridor and asked them if they planned to discard the old [school] tie any time soon. They looked at me like I was mad and instinctively reached for their stethoscopes; the tie and stethoscope are key identifying symbols of a doctor's status. No tie is a reason why women still don't rise as far or as fast in the medical profession.

Semmelweis was onto this [doctors being a vector for disease as dangerous in context as anopheles mosquitos [malaria] or badgers [TB]) 170 years ago. He obtained his medical doctorate in 1844 choosing to specialise in obstetrics and obtained a prestigious position in Vienna as assistant to Geburtshilfe-Professor Johann Klein. In those days mortality from childbed fever was frighteningly common. We know now that this is due to infection, frequently by Streptococcus pyogenes; but 1846 was long before Pasteur had rubbished the theory of spontaneous generation and forced acceptance of his germ theory of disease. So Semmelweis's guess as to the cause of perinatal infection was as good as anyone else's, but not better. But he was notable in approaching the problem through the gathering of data rather than by reading what Galen or Aristotle had to say on the matter.

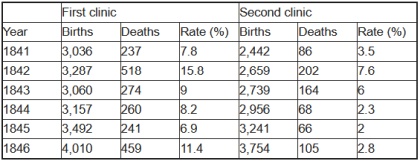

First off he noted that he and Klein were responsible for two clinics which had significantly different rates of mortality:

Convinced that he was right, from 1847 he compelled the students and doctors under his direction to wash their hands with a powerful disinfectant [chlorinated lime, we use it to sanitise swimming pools] between autopsy and delivery and within a month the rate of mortality in the first clinic fell to 10% of its previous high. He didn't know what the agent of death was precisely but knew that chlorinated lime dealt effectively with the smell of death . . . and the results of this simple intervention were compelling.

The response from the medical profession was either a) indifference or b) to reject his theory or c) say that this was already known and so wholly unoriginal. The following year, when his two-year contract ended, it was not renewed and he was forced to return to Budapest. Not before he got into a number of unseemly slanging matches with the medical establishment in Vienna. From Budapest he continued to enforce his hand-washing regime with conspicuous positive effect. But he also continued to barrack his medical colleagues for not seeing things as he saw them. He wrote up his findings and published them 12 years later in 1861 as Die Ätiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers [The etiology, meaning and avoidance of childbed fevers]. He used this also as a vehicle to criticise his critics and so didn't win over anyone who wasn't already convinced. Several unfavorable reviews resulted and Semmelweis responded with a number of intemperate open letters re-asserting his position and insulting his critics in unparliamentary language.

He gradually went off the rails entirely and there has been a lot of post-hoc speculation about the nature of his madness - early-onset Alzheimer's and GPI [general paralysis of the insane = syphilis] from intimate handling of hundreds of prostitutes at work are the front-runners. But let's consider an alternative hypothesis: not mad [bonkers] at all but mad [furious]. Suppose today that you believed in the rights of animals not to be casually consumed in scientific experiments or on the dinner-plate. Suppose you knew you were on the high moral ground on this but that everyone around you considered animals to be unworthy of consideration equal to what was accorded to men. Suppose that this iniquity ate into your soul and you had a tendency to anger. Suppose that nobody would listen to you, especially after you had been insulting about their own professional practice. Wouldn't you be fighting mad?

Eventually his tiresome behaviour got too much for everyone and, at the end of July 1865, he was committed to a Vienna Insane Asylum by János Balassa, a highly respected medical professor from Budapest. Ferdinand Ritter von Hebra, another respectable doctor [Ritter von is "Sir"] agreed to take Semmelweis "to visit a new von Hebra clinic". Semmelweis, in his professional suit and tie, objected most strongly when he realised where he was being delivered and was beaten into submission by the guards, confined in a straitjacket, doused in cold water and purged with castor oil. He died of gangrenous septicaemia two weeks later. Twenty years later, Semmelweis's ideas fell into place as Louis Pasteur made clear that bacteria were the key to most of the contagious diseases which beset us. We're very sorry that we didn't listen to Semmelweis and we've put him on postage stamps, but we're not as sorry as the thousands of women who died in the years between his discovery and its implementation.

No comments:

Post a Comment